For abstracts of invited talks, see Invited Talks.

Mar. 19th (Thu)

On Negative Code Game, the generalization of Code Game

Haruki Wada(Hiroshima University)

Octal games are Nim games in which players are allowed to split a heap into two

in some options, in addition to taking some tokens, and these games are denoted by octal codes. When we

allow the players to split the heaps into more than two heaps, the resulting games are still denoted by

codes (by using digits larger than or equal to 8), and are called Code games. In these codes, the precise

options when taking d tokens are given in the d-th digit of the code. In this talk, we introduce a Negative

Code game, where the players are allowed to add n tokens (or take away (-n) tokens) and split the heap into

more than n+1 heaps. Under this convention, the game always ends in finitely many steps. We present some

interesting examples, such as (16)(8)(4). (2)(1) and (16)4., together with calculations or conjectures of

the Nim-values. Some Negative Code Games can be reduced to Code Games, for example (16)(4). can be reduced

to (0).(7)(31), but not all of them.

Keywords: Code Game, Nim-value, Impartial Game, take and break game

Continim

Yuto Moriwaki(Hiroshima University)

When S is a finite set of positive integers, we can consider classical

Subtraction Nim with S as the set of removable numbers. Even when S consists of three elements, many

questions remain unanswered. For example, we do not have a period formula of the Nim value. In this talk, we

generalize S to be a finite set of positive real numbers. We found that in some regions, we can give

concrete formulae for the period and the Nim value function. To be more precise, when the set S of removable

numbers is S={a, b, 1} satisfying the conditions 0<a<b<1 with b<=2a, we have determined exactly

that for which value (a, b, 1), the Nim value function is purely periodic with the periods a+b, a+1, b+1 or

otherwise, as shown in our material. Even when S consists of integers, these results seem to be new.

Keywords: Subtraction Nim, Nim value, period, preperiod, continuous

parameters

Download File

Reflexivity Criteria and Minimality in Subtraction Games

Takuto Maki(Graduate School of Science and Engineering,

Kagoshima University)

Abstract will be provided soon.

Keywords: TBA

Another Cutcake

Hikaru Hirata(Hiroshima University)

We will discuss Another Cutcake Variant, which appears in Winning Ways, Volume 1,

Chapter 2.

In this game, we start from a rectangle cake of size n x m, and Left chooses one piece of the cake and cuts it vertically v times along the grids in one move, and Right chooses one piece of the cake and cuts it horizontally h times along the grids in one move.

The game values is stated in the text, but is not correct, and we give the correct value in this presentation.

In this game, we start from a rectangle cake of size n x m, and Left chooses one piece of the cake and cuts it vertically v times along the grids in one move, and Right chooses one piece of the cake and cuts it horizontally h times along the grids in one move.

The game values is stated in the text, but is not correct, and we give the correct value in this presentation.

Keywords: Cutcake

The discovery of the surreal numbers (Invited Talk)

Carlos Pereira dos Santos(ISCTE-University Institute of

Lisbon & NovaMath, FCT NOVA, Portugal)

John Horton Conway (1937–2020) was an unconventional mathematician. He made

highly sophisticated contributions across a wide range of fields, demonstrating remarkable skill in

connecting them in astonishing ways. A paradigmatic example is the discovery of the surreal numbers, which,

without exaggeration, can be regarded as a landmark moment in the history of mathematics. This work aims to

explore that moment by providing an intuitive analysis of the crucial aspects of the discovery, as well as

by presenting videos in which Conway himself explains and comments on each of them in his own words. The

result is a non-technical talk, accessible to undergraduate students with some background in mathematics.

Omni-Fission

Sahana Jahagirdar(Indian Institute of Technology

Bombay)

Omni-Fission is a variation of a ruleset implemented in CG Suite played with

black and white stones on an mxn grid with a fixed initial configuration. On a player's turn, they

choose one of their stones and pick a subset of orthogonal empty squares (minimum 2) to expand their stones

on, leaving their original square empty. We present some intriguing results on 1xn boards, along with a

method for generating arbitrarily hot positions. We propose some conjectures regarding game values on a 2xn

board. Inspired by ‘Conway’s Game of Life’, by limiting to maximum expansion, we determine the winner of

certain starting positions purely from the dimensions of the grid. Such cellular automata-like two-player

games induced by this ruleset pose several interesting research directions.

Keywords: combinatorial game theory, two-player partisan game, grid

game, cellular automata

Divisibility Duel and the Remainders

Madhav Miglani(IIT BOMBAY)

Keywords: Partizan Game, Divisibility , Remainder, Canonical Form

Download File

Computational complexity of biased Undirected Vertex Geography

Kanae Yoshiwatari(Kyoto University)

In (i,j)-biased combinatorial games, the first player makes i moves per turn,

while the second player makes j moves per turn. An (i,j)-biased game can also be interpreted as an n-player

game in which the players are divided into two teams.

In this work, we investigate the computational complexity of (i,j)-biased Undirected Vertex Geography. The classical ((1,1)-biased) Undirected Vertex Geography is known to be solvable in polynomial time, and we are interested in determining when a game that is solvable in polynomial time in the standard (1,1) setting becomes PSPACE-hard as the parameters i and j vary. As a result, we show that (i,j)-biased Undirected Vertex Geography is PSPACE-complete for all cases except (i,j)=(1,1).

In this work, we investigate the computational complexity of (i,j)-biased Undirected Vertex Geography. The classical ((1,1)-biased) Undirected Vertex Geography is known to be solvable in polynomial time, and we are interested in determining when a game that is solvable in polynomial time in the standard (1,1) setting becomes PSPACE-hard as the parameters i and j vary. As a result, we show that (i,j)-biased Undirected Vertex Geography is PSPACE-complete for all cases except (i,j)=(1,1).

Keywords: Computational complexity, Geography

Slime Trail is PSPACE-hard on grids

Matt Ferland(Dickinson College)

Slime Trail is a two-player combinatorial game created by Bill Taylor in 1992

that has gained significant popularity, particularly in Portugal where it has been featured in annual

mathematical game tournaments organized by Ludus since 2008. The game is played on a graph where players

alternate moving a token between vertices, leaving a “slime trail” that prevents future moves to visited

vertices.

It has been previously proven that it is PSPACE-complete on planar graphs, but this talk covers an extension to demonstrate it is PSPACE-complete even on grids.

It has been previously proven that it is PSPACE-complete on planar graphs, but this talk covers an extension to demonstrate it is PSPACE-complete even on grids.

Misère Partizan Arc Kayles is PSPACE-complete

Kyle Burke(Florida Southern College)

We show that Misère Partizan Arc Kayles is PSPACE -complete on planar graphs via

a reduction from Bounded Two-Player Constraint Logic. With the planarity, it is easy to extend the result to

colored edge graphs embedded in the square and triangular grids.

Keywords: misère, partizan, computational complexity

Heavenly Domineering

Anuj Jha(IIT Bombay)

This paper introduces Heavenly Domineering, a constrained variant of the

classical partisan game Domineering, in which both players are restricted to placing their dominoes only at

the topmost playable edge of a connected region on a square grid. This limitation simplifies the

combinatorial structure of many traditionally complex Domineering positions, leading to games that are

predominantly cold and easy to calculate the value of explicitly. We compute exact values for a range of

positions, including dyadic rationals as small as 1/8, switches, tinies, and other infinitesimals such as

up, down, and their combinations, and provide thermographic analysis to illustrate thermal behavior.

One of the key themes of the paper is the interaction of geometry with the value of the game: whereas a 90-degree rotation of a classical Domineering position corresponds to negation, the global-top constraint breaks the symmetry, and we investigate to what extent rotation, possibly together with reflection, can still perform negation or other simple value changes in Heavenly.

One of the key themes of the paper is the interaction of geometry with the value of the game: whereas a 90-degree rotation of a classical Domineering position corresponds to negation, the global-top constraint breaks the symmetry, and we investigate to what extent rotation, possibly together with reflection, can still perform negation or other simple value changes in Heavenly.

Keywords: Domineering, Partizan Games, Constrained Play.

Download File

CrissCross – A Domineering Variation

Rakshit Rane(Indian Institute of Technology Bombay

(IITB), Mumbai, India)

Criss-Cross is a two-player partizan game played on an m x n grid and is a

variant of Domineering in which players take turns placing non-overlapping diagonal dominoes. We construct

an explicit affine correspondence between Criss-Cross and standard Domineering positions and show that every

Criss-Cross position is equivalent to the disjunctive sum of two Domineering positions. We conjecture that

every empty m x n board with both dimensions odd is an N-position, with game value always equal to ∗, a

switch, or ∗ plus switch, and no other values appear in the cases we have examined. We also show that the

construction underlying the classical snake positions in Domineering carries over to Criss-Cross, producing

a closely related family of dyadic values.

Keywords: Partizan play, diagonal dominoes, Domineering, game

equivalence, explicit construction, conjecture, N-position, snake positions, dyadic values

Download File

Various Diamond Properties in Combinatorial Game Theory

Tomoaki Abuku(Gifu University)

We investigate conditions under which positions in combinatorial games admit

simple values.

We introduce a unified diamond framework, called the diamond property for integers and dyadic rational numbers.

Under certain conditions, this framework guarantees that all values of positions closed under options are pairs of the form {m | n}, where m and n are integers or dyadic rational numbers.

As an application, we establish that every position in the Yashima game on bipartite graphs has an integer pair value.

We introduce a unified diamond framework, called the diamond property for integers and dyadic rational numbers.

Under certain conditions, this framework guarantees that all values of positions closed under options are pairs of the form {m | n}, where m and n are integers or dyadic rational numbers.

As an application, we establish that every position in the Yashima game on bipartite graphs has an integer pair value.

Keywords: Combinatorial Game Theory, Diamond Property, Yashima Game

Tap and Top Match

Divye Goyal(IIT Bombay, India)

There is a well-known game called Chopsticks, also known as Survival Finger. In

this report, we study two finite variations of it, called Top Match and Tap Match. Players move by tapping

an opponent’s hand, thereby increasing the number of pieces until it exceeds the vanish level. While Tap

Match remains faithful to the classical all-small variant, Top Match introduces a restriction on tapping

based on strength.

In Top Match, we prove that the temperature of every game position is bounded above by 1 and identify a subclass of positions that are always either P or R. In Tap Match, we show that for any vanish level n, the atomic weights are strictly less than n. Furthermore, we construct a sequence of positions capable of achieving any arbitrarily large atomic weight.

In Top Match, we prove that the temperature of every game position is bounded above by 1 and identify a subclass of positions that are always either P or R. In Tap Match, we show that for any vanish level n, the atomic weights are strictly less than n. Furthermore, we construct a sequence of positions capable of achieving any arbitrarily large atomic weight.

Keywords: Chopsticks, Atomic Weight, Temperature Theory

Fission and CoolFission

Nikhil Nagaria(Indian Statistical Institute,

Bangalore)

Fission is a simple combinatorial game played on a rectangular grid with stones

placed in an alternating pattern. Left plays by "vertically" splitting a stone into two that land

on empty spaces above and below that stone, and Right does the same but "horizontally". One can

see CGSuite for reference, where the ruleset is already implemented. In this presentation, we'll

explore some basic results about the game values in normal play, in particular, values of 1-by-n and 2-by-n

grids, and results about larger grids. We will also look into an all-small variation, called CoolFission and

the equivalence of some of its positions with positions in the famous Dawson's Kayles.

Download File

Full and Truncated Support Subtraction

Ankita Dargad(Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay,

India)

We investigate Full Support Subtraction (FSS), a subtraction game in which the

players can remove any number of pebbles from the heap up to certain bounds that are typically different for

Left and Right. The player with the richer move set always wins for all but finitely many heap sizes. We

confirm this advantage by finding the general canonical form and the atomic weights of this game.

To restore fairness (and peace), we introduce Truncated Support Subtraction (TSS), which trims the larger subtraction set from below. As the cuts deepen, the game begins producing infinitely many P- and N-positions. However, if the truncation is shallow, the unfairness persists above a certain heap size, and one player continues ruling. We also explore the atomic weights for these lightly trimmed scenarios.

To restore fairness (and peace), we introduce Truncated Support Subtraction (TSS), which trims the larger subtraction set from below. As the cuts deepen, the game begins producing infinitely many P- and N-positions. However, if the truncation is shallow, the unfairness persists above a certain heap size, and one player continues ruling. We also explore the atomic weights for these lightly trimmed scenarios.

Keywords: Combinatorial game, Partizan subtraction games, Canonical

forms, Atomic weights, P-positions and N-positions

Updates on atomic variations of Roll the Lawn and Cricket Pitch

Mike Fisher(West Chester University)

Nowakowski and Ottaway introduced two games in a 2011 paper as examples of

option-closed games. The first game is Roll the Lawn, and it uses a row of bumps (nonnegative integers) and

a roller that is either between two bumps or at one end of the row. Left moves the roller to the left

flattening each bump by 1 unless the bump has been flattened to 0 in which case nothing happens to that

bump. For a move to be legal, at least one bump must be flattened by 1. Right moves the roller to the right,

with the same effect and constraint. In Cricket Pitch, there's an extra constraint: the roller cannot

go over a bump that has already been flattened to 0. For two of the variations considered in this talk, we

imagine that the bumps are green Hackenbush stalks. In addition to the rules above, we allow each player to

make a Nim move on any one Hackenbush stalk of nonzero height. As the canonical forms become complicated

very quickly, we instead provide a formula for the atomic weight of a given position. The next

generalization considered is a variant of Roll the Lawn. In this variant, we replace the roller with a fence

which Left may move to the right over any number of stalks, reducing each nonzero stalk by one edge as it

moves over it. Left may also make a Nim move on any one nonzero stalk on her side of the fence. Right's

moves are similar. Our final variation is like the one above, but it includes the Cricket Pitch restriction.

As with the other two variations, canonical forms quickly become messy. Thus, we turn to atomic weight to

make sense of the game.

Keywords: atomic weight

A normal play – Chain Reaction

Somya Dahiaya(Indian Institute of Technology,

Bombay)

Chain Reaction is a well-known combinatorial game played on a finite grid. In

this report, we study two terminating variations of the game, called Stacking Attackers and Blocking

Attackers. While Blocking Attackers is an all-small game, Stacking Attackers exhibits partizan behavior. In

the partizan version, attackers are formed according to the threshold value of a tile, whereas in the

all-small version, opponents block each other’s attackers by means of a common shared piece.

In the partizan version, we analyze the game values arising from small board configurations and show that dyadic rational values occur up to 1/8, but no dyadic values beyond 1/8 are attainable. Furthermore, we derive a systematic method for constructing infinitesimal game values, generating the sequence from tiny_2 through tiny_9.

In the all-small version, we investigate the atomic weights of positions and present a construction that produces boards with arbitrary integral atomic weight.

In the partizan version, we analyze the game values arising from small board configurations and show that dyadic rational values occur up to 1/8, but no dyadic values beyond 1/8 are attainable. Furthermore, we derive a systematic method for constructing infinitesimal game values, generating the sequence from tiny_2 through tiny_9.

In the all-small version, we investigate the atomic weights of positions and present a construction that produces boards with arbitrary integral atomic weight.

Keywords: Dyadics, Infinitesimals, Atomic Weights

Mar. 20th (Fri)

A Nim with Two Different Rules

Kikuno Ooyagi(Keimei Gakuin Junior and High

School)

We study a game of Nim with two different rules. If the number of stones

satisfies a specific condition, players play according to the first rule; otherwise, they play according to

the second rule. Let n,m be natural numbers. We consider a three-pile NIM, and we denote by x,y,z the number

of stones in the first, second, and third pile. Without any loss of generality, we assume that x <= y

<= z . In the first game, we play according to the rule of the traditional three-pile NIM when x,y,z =

2^n. Then, the set of P-positions is the union of three sets {(0,x,x):x=0,1,… }, {(x,y,z): the nim sum of

x, y, z is 0 and x,y,z <2^n }, and {(x,y,z):x= 2^n }. Therefore, the set of P-positions is a simple

mixture of the traditional NIM and the Greedy NIM. In the second game, we play according to the traditional

three-pile NIM when x,y,z = 2^n+1. Then, the set of P-positions is the union of four sets {(0,x,x):x=0,1,…

}, {(x,y,z): the nim-sum of x,y,z, = 0 and x,y,z <2^n+1}, {(x,y,z):x= 2^n+1 }-

{(m,2^n+1,2^n+1):m=1,2,..,2^n}, and {(m,2^n,2^n+1):m=2,3,…,2^n-1}. We also study a game of Nim with two

different rules by introducing a pass move. Then, we get a game that is very similar to the traditional NIM,

and this game has a formula for the set of P-positions when a pass is allowed.

Keywords: NIM two rules

Download File

Periodicity of m-Pile Divisor Nim

Takayuki Morisawa(Kogakuin University)

Makino defined 2-pile divisor Nim as a variation of 2-pile Nim.

Its rule is that the player removes d stones from a pile where d divides the number of stones in the other pile.

In this talk, we generalize it to m-pile divisor Nim and show that the Sprague-Grundy value is periodic.

Its rule is that the player removes d stones from a pile where d divides the number of stones in the other pile.

In this talk, we generalize it to m-pile divisor Nim and show that the Sprague-Grundy value is periodic.

Keywords: Nim, Sprague-Grundy value, Divisor, Period

Conway’s Field of Characteristic 2 and the Algorithms for Its Operations (Invited Talk)

Ko Sakai

Conway proved that the class of all ordinal numbers forms a field of

characteristic 2 by introducing the Nim sum and the Nim product operations. This lecture will present

algorithms for performing these operations and discuss methods for solving algebraic equations in this

field.

Mind the gap: A real-valued distance on combinatorial games

Craig Tennenhouse(University of New England, USA)

We define a real-valued distance metric wd on the space C of short combinatorial

games in canonical form. We demonstrate the existence of Cauchy sequences informed by sidling sequences,

find limit points, and investigate the closure of C, which is shown to partition the set of loopy games in a

non-trivial way. Stoppers, enders, and non-stopper-sided loopy games are explored, as well as the

topological properties of (C,wd).

Keywords: cauchy sequences, distance metric, combinatorial games

Crushcar Nim

Kouta Kawakami(Hiroshima University)

We will discuss Crushcar Nim. There are some piles of tokens with indices, and

the player chooses a pile and takes at least 1 token from the pile. Then, she/he can add tokens to the piles

with smaller index. For example, one can play (2,3,1,5) to (2,0,3,2026). We show that the Grundy number

takes transfinite value, and to express it in base (ω2) is more natural than to express it in base ω.

We also show that this game is tame. In other words, if Normal Grundy number g(x)>1, then misère Grundy number g’(x)=g(x).

We also show that this game is tame. In other words, if Normal Grundy number g(x)>1, then misère Grundy number g’(x)=g(x).

Keywords: Impartial game,Transfinite Grundy number, Nim, Tame

Asymmetric Wythoff's Game

Hiyu Inoue(Hiroshima University)

I consider a generalization of Wythoff's Game, where the two piles are

treated unequally. Let m and n be integers greater than or equal to 1. In this game, there are two piles of

tokens, and a player is allowed to take one or more tokens from a single pile, or to take i tokens from the

first pile and j tokens from the second pile such that i-n < j < i+m. The case n=m=1 corresponds to

the classical Wythoff's Game. I investigated the P-positions under both normal play and misère play and

proved that the P-positions can be described by two Beatty Sequences. Furthermore, as in previous studies,

the P-positions can have a mex discription and also a Zeckendorf style discription.

Keywords: Wythoff's Game, Beatty Sequence, Rayleigh's

Theorem, mex, continued fraction

Triangular Nim with S-Wythoff twist

Kosaku Watanabe(Hiroshima University)

Triangular Nim is a variant of two-heaps Nim in which the players take at least

two tokens from one heap and return at least one tokens to the other heap, so that the total number of

tokens decreases. When we also allow the Wythoff option, namely the players can take the same number of

tokens from both heaps, then the P-positions of the game with x 0, and the players are allowed to take i

tokens and j tokens respectively from each heap, when |i-j|<s_Min(i, j), then not only triangular numbers

but also various interesting sequences appear in the description of P-positions. Conversely when we give a

sequence of positive integers satisfying certain conditions, then we can apply an algorithm to produce S

from which the given sequence appears. When S={1, 1, 1, …}, we have the triangular numbers, when S={1, 2,

3, 4, …}, we have the Mersenne numbers {1, 3, 7, 15, …}. We can apply our algorithm also to many

polynomial functions like power sums, and the factorial function n!, and a lot more. If we allow 0 for the

elements of S, then we can also make a game where the Fibonacci Sequence appears in the description.

Keywords: impartial game, Wythoff Nim, Triangular Nim, polygonal

numbers, recurrence relation

Asymmetric Triangular Wythoff Nim

Kosaku Watanabe(Hiroshima University)

Triangular c-Wythoff Nim is a variant of two-heaps Nim. This game allows two

types of options: (1) The players take at least two tokens from one heap and return at least one token to

the other heap so that the total number of tokens decreases; (2) the players take tokens from both heaps in

such a way that the difference between the removed tokens is less than a constant c. The P-positions of this

game are described by consecutive (c+2)-gonal numbers, say (0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 3), (3, 6), …. when c=1 and

x<=y,

In this talk, we introduce, still impartial but an asymmetric variant of the Triangular Wythoff Nim with two positive integers, say (a, b), where the legal options depend on the heap. In this game, the P-positions are described by (a+2)-gonal numbers and (b+2)-gonal numbers. For example when a=1 and b=2, the P-positions are (0, 0),(0, 1), (1, 4), (3, 9), (6, 16), (10, 25), …, for 2x=y. Moreover, for some choices of the parameters (a, b), for example (1, 3), the total number of tokens may increase, and this game becomes loopy, even though all positions are either P or N-positions, and the winning side can finish the game in finite moves. If the players do not care about winning, they can play this game forever for such parameters.

In this talk, we introduce, still impartial but an asymmetric variant of the Triangular Wythoff Nim with two positive integers, say (a, b), where the legal options depend on the heap. In this game, the P-positions are described by (a+2)-gonal numbers and (b+2)-gonal numbers. For example when a=1 and b=2, the P-positions are (0, 0),(0, 1), (1, 4), (3, 9), (6, 16), (10, 25), …, for 2x=y. Moreover, for some choices of the parameters (a, b), for example (1, 3), the total number of tokens may increase, and this game becomes loopy, even though all positions are either P or N-positions, and the winning side can finish the game in finite moves. If the players do not care about winning, they can play this game forever for such parameters.

Keywords: impartial game, Wythoff Nim, Triangular Nim, polygonal

numbers, loopy game

TBA

Takahiro Yamashita(Hiroshima University)

Abstract will be provided soon.

Keywords: Impartial game, Wythoff Nim, Triangular Nim, TBA

A Variant of Wythoff's Game Whose Misere Version Is Almost the Same as

Wythoff's Game

Aoi Murakami(Kwansei Gakuin University)

We consider a variant of the classical Wythoff's game. The classical form is

played with two piles of stones, from which two players take turns to remove stones from one or both piles.

When removing stones from both piles, an equal number must be removed from each. The player who removes the

last stone or stones is the winner.

In this variant, the terminal set is {(x, y): x + y =8 or y >= 8. The second one is that there is an essential relation between this variant and Hofstadter's G-Sequence.

Let a_1(n) and a_2(n) are integer sequences such that

{(a_1(n),a_2(n)):n=0,1,2,…} cup {(a_2(n), a_1(n)):n=0,1,2…} is the set of P-positions of the classical Wythoff's game.

We define a variant of Wythoff's game by using {(x,y):x+y <=2} as the terminal set.

Then there exists an integer-valued function g(n) and

if we let b_1(n) =a_1(n)+g(n)-1 and b_2(n)) = a_2(n)+g(n), then

{(b_1(n),b_2(n)):n=0,1,2,…} cup {(b_2(n), b_1(n)):n=0,1,2…} are the set of P-positions of the variant. By using Hofstadter's G-Sequence, we can define this function g(n).

The third one is that the sequence {b_(n+1)-b_(n):n=1,2,…} has a self-similarity.

In this variant, the terminal set is {(x, y): x + y =8 or y >= 8. The second one is that there is an essential relation between this variant and Hofstadter's G-Sequence.

Let a_1(n) and a_2(n) are integer sequences such that

{(a_1(n),a_2(n)):n=0,1,2,…} cup {(a_2(n), a_1(n)):n=0,1,2…} is the set of P-positions of the classical Wythoff's game.

We define a variant of Wythoff's game by using {(x,y):x+y <=2} as the terminal set.

Then there exists an integer-valued function g(n) and

if we let b_1(n) =a_1(n)+g(n)-1 and b_2(n)) = a_2(n)+g(n), then

{(b_1(n),b_2(n)):n=0,1,2,…} cup {(b_2(n), b_1(n)):n=0,1,2…} are the set of P-positions of the variant. By using Hofstadter's G-Sequence, we can define this function g(n).

The third one is that the sequence {b_(n+1)-b_(n):n=1,2,…} has a self-similarity.

Keywords: Wythoff's game, Hofstadter's G-Sequence

Download File

Cyclic Sink Subtraction

Anjali Bhagat(Indian Institute of Technology Bombay,

India)

We study impartial subtraction games played on circular game boards by defining

various widths of {\em sinks}, which correspond to terminating P-positions. This approach allows positions

to undergo multiple cycles before settling on definitive game values. We examine these games in the context

of Smith-Fraenkel-Yesha generalized Sprague-Grundy values and demonstrate that patterns ultimately stabilize

as we expand the cycles at regular intervals, a phenomenon we term expansion periodicity. Furthermore, we

conjecture that these expansion periods are independent of sink size and cycle lengths, and that they settle

at a divisor of the period length induced by the sink width of non-cyclic play.

Keywords: Cyclic Impartial Game, Sink, Smith-Fraenkel-Yesha Theory,

Subtraction Game

Additive Sink Subtraction (Invited Talk)

Urban Larsson(IEOR, IIT Bombay)

Subtraction games belong to the folklore of Combinatorial Game Theory (CGT). In

particular, a classical result of Golomb (1966) shows that every subtraction game with a finite move set has

an eventually periodic nimber sequence. From this perspective, subtraction games are often regarded as

“solved”. However, this result provides only an exponential upper bound on the period length, while most

studied rulesets have polynomial (small degree) period lengths. Very few general results are known

concerning explicit formulas for given ruleset families. Through extensive computational experiments,

remarkably, Flammenkamp (PhD thesis, 1996) identifies subtraction sets S with as few as five moves whose

outcome-period lengths appear to grow as large as ∼2^{0.3 max S}. He also formulates a conjecture for

three-move subtraction games, for which a striking experimental classification emerges: non-additive sets

exhibit linear period lengths of the form “the sum of two moves”, although the choice of which two moves

displays fractal-like behavior, whereas additive sets S = {a, b, a + b} have purely periodic outcomes with

conjectured linear or quadratic period lengths. Additive subtraction games receive special attention already

in *Winning Ways* (1982), where a specific family with linear period lengths is solved. However, contrary to

a statement in Flammenkamp’s thesis, to the best of our knowledge the general additive case in the standard

setting remains open (see also Ward’s more recent arXiv post).

In this talk, we introduce and analyze a dual setting, which we call sink subtraction. In contrast to the standard “wall” convention, where moves to negative positions are forbidden, the sink convention declares a player the winner as soon as they move to any non-positive position (normal play). This winning convention has not yet received much attention, except for a related generalization appearing in Miklós et al. (2024), where three-move games under specific terminal “seeds” are shown to attain super-polynomial, though still sub-exponential, period lengths. A fundamental structural difference is that the wall convention enforces finite play, whereas the sink convention allows circular play for finite sinks; see Bhagat’s talk at this conference. In celebration of this added generality, we demonstrate that additive sink subtraction, with an infinite sink, admits a complete solution: the nimber sequence is purely periodic with an explicit (linear or) quadratic period formula. Strikingly, this formula exhibits “dual” properties to the conjectured period formula for additive wall subtraction; see Manabe’s talk at this conference.

In this talk, we introduce and analyze a dual setting, which we call sink subtraction. In contrast to the standard “wall” convention, where moves to negative positions are forbidden, the sink convention declares a player the winner as soon as they move to any non-positive position (normal play). This winning convention has not yet received much attention, except for a related generalization appearing in Miklós et al. (2024), where three-move games under specific terminal “seeds” are shown to attain super-polynomial, though still sub-exponential, period lengths. A fundamental structural difference is that the wall convention enforces finite play, whereas the sink convention allows circular play for finite sinks; see Bhagat’s talk at this conference. In celebration of this added generality, we demonstrate that additive sink subtraction, with an infinite sink, admits a complete solution: the nimber sequence is purely periodic with an explicit (linear or) quadratic period formula. Strikingly, this formula exhibits “dual” properties to the conjectured period formula for additive wall subtraction; see Manabe’s talk at this conference.

Keywords: Additive Game, Nimber, Periodicity, Sink Convention,

Subtraction Game

Duality between Sink and Wall Subtraction Games

Hikaru Manabe(University of Tsukuba)

Standard subtraction games, played under the classical 'wall'

convention (where moves to negative positions are forbidden), have been studied for decades. While the

eventual periodicity of their nimber sequences have proved, the explicit structure of these periods remains

an open problem. As highlighted in the talk by Prof. Larsson, the periodicity of additive subtraction sets

S={a,b,a+b} under the wall convention has been the subject of conjectures by Flammenkamp (1996), yet a

complete proof for the general case has remained open.

In this talk, we present a fundamental correspondence between the wall convention and the 'sink' convention introduced in the previous talks. We show that, remarkably, the nimber sequence of a subtraction game under the wall convention exhibits a precise structural duality with that of the corresponding sink game. By leveraging Prof. Larsson's complete solution for the additive sink subtraction games, this duality allows us to determine the period structure of some additive wall subtraction games, thereby affirming and extending the long-standing conjectures regarding their behavior.

We will discuss the mechanism of this duality and outline the proof strategy that bridges the gap between the solvable sink setting and the classical wall setting.

In this talk, we present a fundamental correspondence between the wall convention and the 'sink' convention introduced in the previous talks. We show that, remarkably, the nimber sequence of a subtraction game under the wall convention exhibits a precise structural duality with that of the corresponding sink game. By leveraging Prof. Larsson's complete solution for the additive sink subtraction games, this duality allows us to determine the period structure of some additive wall subtraction games, thereby affirming and extending the long-standing conjectures regarding their behavior.

We will discuss the mechanism of this duality and outline the proof strategy that bridges the gap between the solvable sink setting and the classical wall setting.

Keywords: Impartial Games, Restricted Nim, Subtraction Game

Drop Two Rooks

Hikaru Manabe(University of Tsukuba)

We define a new game "Drop Two Rooks". Two coins are placed on a

chessboard of unbounded size, and two players take turns choosing one of the coins and moving it. Coins are

to be moved to the left or upward vertically as far as desired. If a coin is dropped off the board, players

cannot use this coin. For non-negative integers w,x,y,z, by (w,x,y,z) we denote the positions of the two

coins, where (w,x) is the position of one coin and (y,z) is the position of the other coin. If xy=0 or zw=0,

then the coin denoted by (x,y) or the coin denoted by (z,w) is outside of the chessboard. We permit a jump

over another, but not on another coin. We consider two games. In the first game, if two coins are on the

same vertical or horizontal line, a player can push a coin by another coin and drop both of coins outside of

chessboard to win the game. Then, the set of P-positions of this game is

{(w,x,y,z):the nim-sum of (w-1),(x-1), (y-1), and (z-1) is 0}. In the second game, if two coins are side by side on the same vertical or horizontal line, a player can push a coin by another and drop both of coins outside of chessboard to win the game. Let N_0={(x +- 1,y +- 1, x -+ 1, y -+ 1): x,y = 2,3 mod 4 } cup {(x +- 1,y -+ 1, x -+ 1, y +- 1): x,y = 2,3 mod 4 },

P_1={(x-1,y,x+1,y): x = 2,3 mod 4 } cup {(x, y-1, x, y+1): y = 2,3 mod 4 }

cup {(x, y+1, x, y-1): y = 2,3 mod 4 } cup {(x, y+1, x, y-1): y = 2,3 mod 4 }.

Then, the set of P-positions of this game is

P={(w,x,y,z): the nim-sum of (w-1),(x-1), (y-1), and (z-1) is 0 and wxyz>0}cup P_1 – N_0.

{(w,x,y,z):the nim-sum of (w-1),(x-1), (y-1), and (z-1) is 0}. In the second game, if two coins are side by side on the same vertical or horizontal line, a player can push a coin by another and drop both of coins outside of chessboard to win the game. Let N_0={(x +- 1,y +- 1, x -+ 1, y -+ 1): x,y = 2,3 mod 4 } cup {(x +- 1,y -+ 1, x -+ 1, y +- 1): x,y = 2,3 mod 4 },

P_1={(x-1,y,x+1,y): x = 2,3 mod 4 } cup {(x, y-1, x, y+1): y = 2,3 mod 4 }

cup {(x, y+1, x, y-1): y = 2,3 mod 4 } cup {(x, y+1, x, y-1): y = 2,3 mod 4 }.

Then, the set of P-positions of this game is

P={(w,x,y,z): the nim-sum of (w-1),(x-1), (y-1), and (z-1) is 0 and wxyz>0}cup P_1 – N_0.

Keywords: Two Rooks, P-positions

Download File

Mar 21st (Sat)

A New Approach to the Analysis of Variants of Nim in Misère Play

Nanako Omiya(Tohoku University)

We introduce a method for analyzing the misère version of variants of Nim from a

novel perspective and present results obtained from an analysis of several variants of Greedy Nim in misère

play, for which this method proved particularly effective.

Keywords: Combinatorial Game, Nim, Misère play, Greedy Nim

Game values and quotients for LR-ending partizan games

Hiroki Inazu(Hiroshima University)

We consider an Ending Partizan Subtraction Nim, whose options are the same as

impartial Subtraction Nim, but the winner is determined in a partizan way by the terminal position at which

the game ends.

We concentrate on the LR-type convention, namely, Left wins if the total number of remaining tokens is even, and Right wins otherwise.

To analyze game positions, for impartial games under normal convention, Conway used the notation like 0 = {|}, 1 = {0|} etc., and defined game values as the equivalence class of game positions where G and H are identified if and only if the outcome of G + X is same as H + X for each game position X. We have a criterion that says G and H have the same game value if and only if the outcome of G – H is P, hence we don't really need to test with X. For Misere convention, Plambeck and Siegel proposed Misere Quotient, where the test positions X are restricted. In this talk, we generalize both Conway type notations/game values and Quotients, for LR-type convention. Some games can be completely analyzed by combining these two techniques. We also compare these “game values” for LR-type with Nowakowski normal interpretation, where, for example the game ends with even number of tokens, instead of declaring Left as the winner, we allow only Left the final extra move. We can use G – H criterion for this interpretation, and its behavior is very similar to our game values but is decisively different when it comes to addition of games.

We concentrate on the LR-type convention, namely, Left wins if the total number of remaining tokens is even, and Right wins otherwise.

To analyze game positions, for impartial games under normal convention, Conway used the notation like 0 = {|}, 1 = {0|} etc., and defined game values as the equivalence class of game positions where G and H are identified if and only if the outcome of G + X is same as H + X for each game position X. We have a criterion that says G and H have the same game value if and only if the outcome of G – H is P, hence we don't really need to test with X. For Misere convention, Plambeck and Siegel proposed Misere Quotient, where the test positions X are restricted. In this talk, we generalize both Conway type notations/game values and Quotients, for LR-type convention. Some games can be completely analyzed by combining these two techniques. We also compare these “game values” for LR-type with Nowakowski normal interpretation, where, for example the game ends with even number of tokens, instead of declaring Left as the winner, we allow only Left the final extra move. We can use G – H criterion for this interpretation, and its behavior is very similar to our game values but is decisively different when it comes to addition of games.

Keywords: game values, quotients, Ending Partizan, Subtraction Nim

Variations of Greedy Nim

Shun-ichi Kimura(Hiroshima University)

Inspired by the works of Nanako Omiya at Tohoku University, we investigated

several variations of Greedy Nim, incluiding Nezumi-Kozo Nim, named after Japanese Robin Hood, who steals

money from rich people and distributs it to poor people (is this really greedy?). We also consider Second

Greedy Nim, where the player can take tokens not only from the piles of the most tokens, but also from the

piles with the second most tokens.

Keywords: Greedy Nim, Grundy Number

Development of Ending Partizan Nim

Shun-ichi Kimura(Hiroshima University)

In this joint work with Hiroki Inazu inspired by his joint work of Koki Suetsugu,

we tried to formalize Ending Partizan Nim with inner disjunctive sum, and discovered amazing phenomenon that

disjunctive sum can be not commutative, and sometimes not even associative.

Keywords: Ending Partizan, Quotient, Foundation of Combinatorial Game

Theory

A Game of Nim with a Forced Pass

Ryohei Miyadera(Keimei Gakuin Junior and High

School)

We study the game of Nim with a forced pass. In combinatorial games, if the

standard rules of the game are modified to allow a one-time pass, that is, a passing move that may be used

at most once in the game and not from a terminal position, and once either player has used a pass, it is no

longer available, the game's underlying structure changes significantly, increasing its complexity. The

authors studied games with a pass and published their findings. In this paper, we present a variant of

pass-move, namely a forced pass. A forced pass is a pass that can be forced on the opponent by one of the

players. In this paper, we study traditional Nim, traditional Nim with a restriction on the number of stones

to be removed, and Greedy Nim under the forced-pass rule. We also study traditional Nim with a restricted

forced pass. If Player A forced a pass on Player B, Player A can play twice. To play twice is a mighty move,

and understandably, the set of P-positions (the previous player's winning positions) is relatively

small compared to the set of N-positions (the next player's winning positions). First, we study the

traditional three-pile Nim with a forced pass, and prove that the set of P-positions is very simple. Next,

we study the three-pile Nim, in which the number of stones to be removed is at least one and at most m,

where m is a fixed natural number. When we introduce a forced pass for this Nim, the set of P-positions is

simple when there is no natural number k such that m=2^k. When there is a natural number k such that m=2^k,

the set of P-positions is complicated. Next, we study the case where we remove only an even number of stones

twice when we force a pass to the opponent. Then, we can describe the set of P-positions with nim-sum.

Keywords: forced pass, P-position

Download File

How high can you go? Finding transfinite game values in infinite Capture Go

Ethan Saunders(University of Calgary)

Capture go is a variant of Go in which the first player to capture a stone wins.

On a finite Go board, we can make "win in k" puzzles — positions where Black is winning and White

can prolong the game for at most k moves. If we let the board be arbitrarily large, we can construct win in

k puzzles for arbitrarily large k. On an infinite Go board, there are even more possibilities. We can

imagine a position on an infinite board in which Black will win in a finite number of moves, but on

White's first move White decides what that finite number is. We could describe such a situation as a

"win in omega" for Black. Similarly, each position in infinite capture go which will end in a

finite number of moves under optimal play can be assigned an ordinal number. The omega one of capture go is

the supremum of this set of ordinals. We will present the problem of finding the omega one of infinite

capture go as well as some progress towards solving it. Joint work with Isobel Shaw.

Combinatorial Game Theory Applying Go Endgames (Invited Talk)

Takenobu Takizawa

Professor Berlekamp and his research group started to apply Combinatorial Game

Theory to mathematical Go endgames in the 1990s. The author joined the group around 1991. We studied

small-area (room) analysis without kos and with kos. Small-area analysis without kos is relatively

easy.

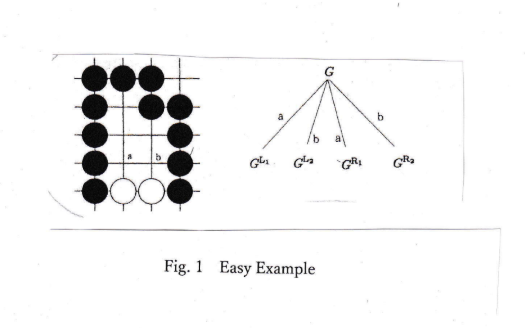

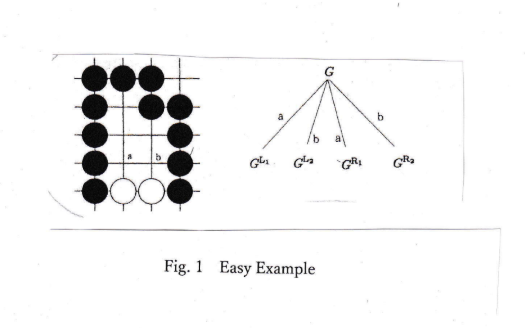

1. Example without kos

Fig.1 shows an easy example of endgame of Go. Both Black and White may play a or b.

The outcome of chilled game of G is G-1. G*1 is defined by Y{ G^L-1 I G^R +1 Y}.

-1 or + 1 is TAX for white (black) because it is usually get one point each for one move in end

stage of Endgame of Go. Under this hypothesis, Fig 1 is analyzed that

G.L=¥{2+1/8,2+up 13/4,1/2¥}=¥{2+1/811/2¥}=1+1/4.

2. Simple 1-point ko

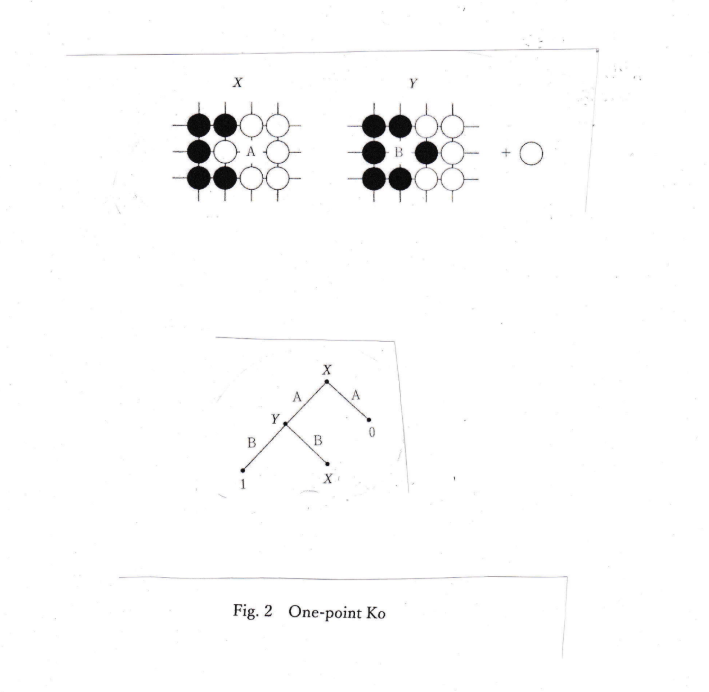

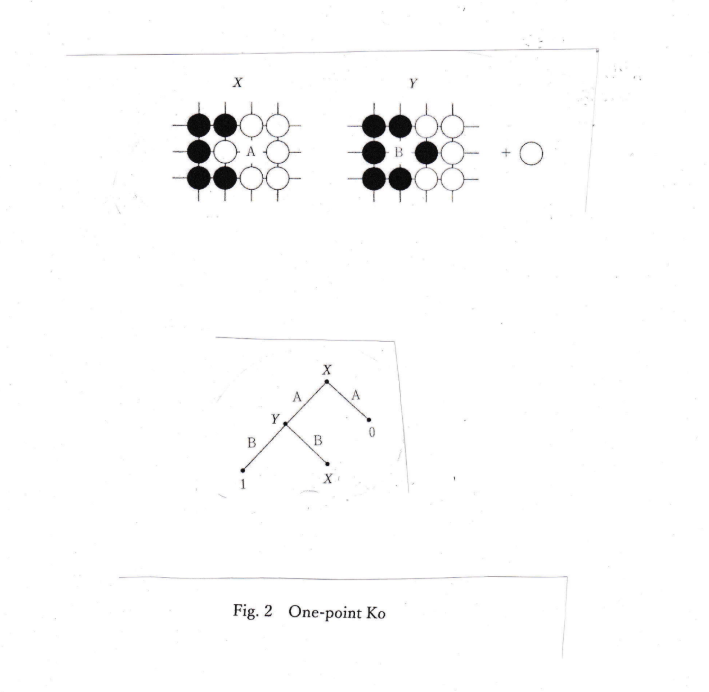

Fig.2 shows a simple 1-point ko. If Black’s turn, he may play the ko and take a stone.

White may not take back the ko immediately. If White plays another place X and Black

responds there, then White may take back the ko. X is called a ko-threat.

3. Ko-master

When there is a ko, Black or White eventually filles the ko. The filling side is the winner

of the ko and cailed ko-master. Note that ko-master must fill the ko.

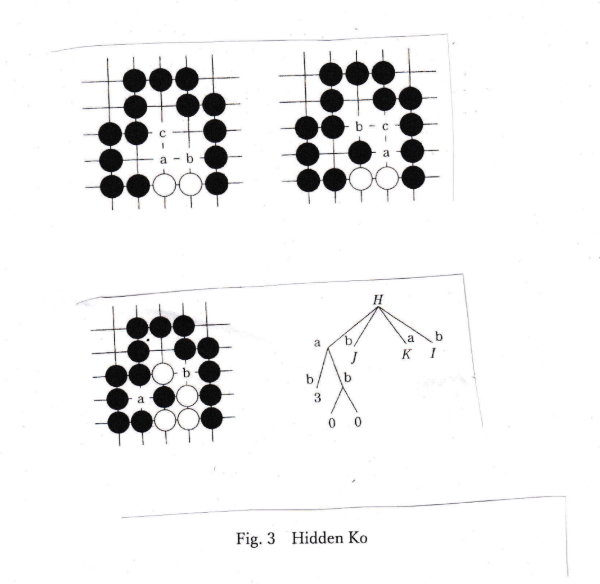

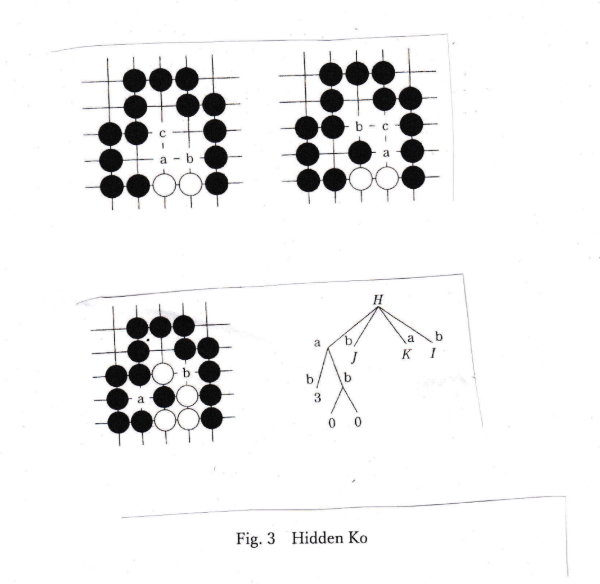

4. Hidden Ko position

Fig. 3 shows a hidden-ko. There are no kos. But, after couple of plays, there might be a

ko. Thie type of ko is calied hidden ko.

5. Rogue Positions

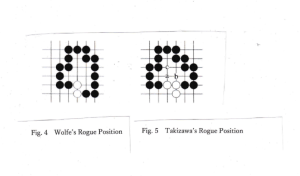

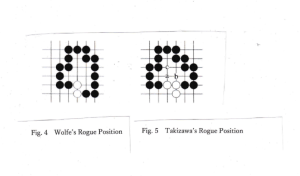

There are interesting positions called Rogue Positions including hidden Ko

5.1 Wolfe’s Rogue posirion

Fig.4 shows Wolfe’S Rogue position.

5.2 Takizawa’s Rogue position

Fig. 5 shows Takizawa’s Rogue position.

1. Example without kos

Fig.1 shows an easy example of endgame of Go. Both Black and White may play a or b.

The outcome of chilled game of G is G-1. G*1 is defined by Y{ G^L-1 I G^R +1 Y}.

-1 or + 1 is TAX for white (black) because it is usually get one point each for one move in end

stage of Endgame of Go. Under this hypothesis, Fig 1 is analyzed that

G.L=¥{2+1/8,2+up 13/4,1/2¥}=¥{2+1/811/2¥}=1+1/4.

2. Simple 1-point ko

Fig.2 shows a simple 1-point ko. If Black’s turn, he may play the ko and take a stone.

White may not take back the ko immediately. If White plays another place X and Black

responds there, then White may take back the ko. X is called a ko-threat.

3. Ko-master

When there is a ko, Black or White eventually filles the ko. The filling side is the winner

of the ko and cailed ko-master. Note that ko-master must fill the ko.

4. Hidden Ko position

Fig. 3 shows a hidden-ko. There are no kos. But, after couple of plays, there might be a

ko. Thie type of ko is calied hidden ko.

5. Rogue Positions

There are interesting positions called Rogue Positions including hidden Ko

5.1 Wolfe’s Rogue posirion

Fig.4 shows Wolfe’S Rogue position.

5.2 Takizawa’s Rogue position

Fig. 5 shows Takizawa’s Rogue position.

Snort temperature compared to maximum degree

Svenja Huntemann(Mount Saint Vincent University)

Snort is a partizan game played on a finite graph in which the players alternate

colouring vertices (Left blue and Right red) such that two vertices of the opposite colours are not

adjacent. And the temperature of a position intuitively represents the urgency of moving first. It is known

that the temperature of Snort is unbounded (e.g. the temperature of the star $K_{1,n}$ is n). We will show

that the temperature can even be unboundedly larger than the maximum degree of the graph and will discuss a

few other questions discussing temperature compared to maximum degree.

Keywords: Snort, temperature

Climb Over: Dyadic Game Values and Elementary Strategies

Nikhil Narera(IIT Bombay)

How complex can a game of stacking boxes be? We introduce Climb Over, a partisan

game where pieces traverse

a 2D grid by climbing over or falling onto adjacent stacks. We show that this interplay between vertical stacking

and horizontal movement is capable of generating all dyadic rational values. We present a constructive proof, detailing a recursive algorithm to build game positions with canonical values 1/2^k. Additionally, we solve the game for fundamental positions with few pieces, revealing that victory in these sparse settings relies on controlling specific parity invariants and managing the relative gaps between pieces.

a 2D grid by climbing over or falling onto adjacent stacks. We show that this interplay between vertical stacking

and horizontal movement is capable of generating all dyadic rational values. We present a constructive proof, detailing a recursive algorithm to build game positions with canonical values 1/2^k. Additionally, we solve the game for fundamental positions with few pieces, revealing that victory in these sparse settings relies on controlling specific parity invariants and managing the relative gaps between pieces.

Keywords: Partisan Game, Dyadic Game, Endgame Analysis, Short Game

Extended Sprague-Grundy value for two-step games -How can you deal with cloning Ninjas?-

Koki Suetsugu(Waseda University, Toyo University, Osaka

Metropolitan University)

In this talk, we consider games in which, some components are given like

disjunctive sum, and only one of them is in the special situation, called "superposition" and the

others are standard positions. The current player makes a move in the superposition and change it to a

standard position. Furthermore, the player selects one of the all standard positions and makes a move. Then,

the position changes to a superposition and the turn ends.

These games cannot be analyzed by the classical Sprague-Grundy theory, however, we show that we can define Sprague-Grundy values for positions in such rulesets by extending Sprague-Grundy theory.

In addition, we introduce some natural rulesets belong to this framework, for example, "Box split game", and "Corner the ninja".

These games cannot be analyzed by the classical Sprague-Grundy theory, however, we show that we can define Sprague-Grundy values for positions in such rulesets by extending Sprague-Grundy theory.

In addition, we introduce some natural rulesets belong to this framework, for example, "Box split game", and "Corner the ninja".

Keywords: Impartial game, Sprague-Grundy value, Delete nim, Two-step

game

Cyclic impartial games with carry-on moves

Alda Carvalho(Universidade Aberta & ISEG

Research)

In an impartial combinatorial game, both players have exactly the same options at

every position of the game. Classical Sprague–Grundy theory provides a fundamental framework for the

analysis of short impartial games, where play is finite, the number of options is limited, and no special

moves occur. Over the years, several extensions of this theory have been developed to address more general

settings. Notably, the Smith–Frankel–Perl theory applies to games in which infinite play is possible, while

the Larsson–Nowakowski–Santos theory accommodates entailing moves that disrupt the usual behavior of the

disjunctive sum.

This talk introduces a generalization that combines these two approaches, making it possible to analyze cyclic impartial games with carry-on moves. Carry-on moves constitute a special class of entailing moves in which the responding player has no freedom of choice. The theory is illustrated through GREEN-LIME HACKENBUSB, a game inspired by the classical game of GREEN HACKENBUSB.

This talk introduces a generalization that combines these two approaches, making it possible to analyze cyclic impartial games with carry-on moves. Carry-on moves constitute a special class of entailing moves in which the responding player has no freedom of choice. The theory is illustrated through GREEN-LIME HACKENBUSB, a game inspired by the classical game of GREEN HACKENBUSB.

Keywords: Entailing moves, games with cycles, impartial games,

Sprague-Grundy Theory, GREEN HACKENBUSB

Ordinal Sums and Poset Games with Initialization

Kengo Hashimoto(University of Fukui)

This presentation considers the following framework in the normal-play

convention. An impartial game is assigned independently to each element x of a finite poset (P, <=). On a

turn, a player selects one element of P and plays the game assigned to it. At that time, for every element y

of P such that y < x, the game assigned to y is replaced with a game H_y, which is fixed in advance for

each element of P.

We show some results on the outcome classes and Grundy numbers for several simple cases. In particular, we analyze a generalization of ordinal sums (G:H) in which, each time G is played, H is replaced with a game J that is fixed in advance.

We show some results on the outcome classes and Grundy numbers for several simple cases. In particular, we analyze a generalization of ordinal sums (G:H) in which, each time G is played, H is replaced with a game J that is fixed in advance.

Keywords: impartial games, ordinal sums, poset games

Construction of Sumbers

Kuo-Yuan Kao(National Penghu University, Taiwan)

In the world of all-small games, many games have integer-valued atomic weight.

The first known family of atomic games are named ups defined as ↑_n={↑_(n-1) |*} (↑_0=0), where n>0 is a

natural number. Thereafter, the family of ups was extended to including ↑_d={↑_(d^L ) |↑_(d^R ),*}, where

d>0 is a number. These ups are totally ordered and each has atomic weight one. Sums of ups and star are

called sumbers, whose outcomes can be determined by a simple rule. This paper extends the family of ups to

including ↑_d^n for all natural number n and number d. The properties of total ordering of ups, unit atomic

weight for each up and simple outcome rule for a sum of ups are all preserved in this extended family of

ups. This paper further claims that if A and B are two sumbers and A-B<| ↑_ω+* (ω={0,1,2,…|}) then {A|B}

is a sumber.

Keywords: combinatorial game theory, all-small games, infinitesimals,

atomic games, ups and downs, sumbers

Download File

The misère invertibility of Amazons and Kōnane

Alfie Davies(Memorial University of Newfoundland)

It is a well-known result of Mesdal and Ottaway that there are no non-zero

invertible games in misère. When we consider restricted misère, however, we can sometimes birth invertible

elements. Most recent work has focussed on studying restrictions to special sets of games called universes;

it is known that the dicot and dead-ending universes both have many invertible games. In this talk, we

consider what are called weak universes, which have no invertible elements (and in fact are even more

restrictive than just this). We then use what we have seen to study the invertible elements of the monoids

of Amazons positions and Kōnane positions. In particular, we show that there are no non-zero invertible

games in both the Amazons and Kōnane monoids.

Keywords: Misère theory, Invertibility, Amazons, Kōnane

Leaning into Misère: Formally, Losing is Hard

Tomasz Maciosowski(Memorial University of

Newfoundland)

Under the misère play condition, the first player who cannot make a move wins.

Most of the structure that exists in normal play, like additive inverses, does not exist in misère play.

Mathlib is a collaborative effort to formalize mathematics using the Lean 4 theorem prover. We have built

upon Mathlib and formalized various results in misère play, yielding more general theorems that capture

transfinite games.

Keywords: Combinatorial Game Theory, Misère, Formalization

Mar. 22nd (Sun)

Evolution of ANI (Artificial Narrow Intelligence) in Shogi and Social Adaptation: A Case

Study for Symbiosis in the Era of ASI (Artificial Super Intelligence)

Kentaro Hoshi(Waseda University, Global Education

Center)

In the domain of Shogi, ANI (Artificial Narrow Intelligence) has already reached

a level that far exceeds human cognitive capabilities. This presentation reports on how the Shogi community

has adapted to this "supra-human ANI" and analyzes it as a preliminary case study for the coming

era of ASI (Artificial Super Intelligence).

Specifically, we discuss two main points. First is the transformation of learning environments and spectator experiences driven by ANI. The widespread adoption of advanced analysis technologies has led to a "democratization of skills," eliminating geographical and environmental disparities. Additionally, the visualization of evaluation scores has opened the "black box" of the game, creating new entertainment value.

Second are the ethical and existential challenges posed by the ubiquity of ANI. The risk of "cheating via AI assistance" has forced a shift from traditional environments based on mutual trust to those requiring strict surveillance systems (Zero Trust). Furthermore, the existence of AI possessing "absolute answers" compels professional players to redefine their value beyond mere victory and defeat, questioning the very meaning of human play.

Through the process of friction and adaptation observed in the Shogi community, this research offers insights into the challenges and possibilities humanity will face in the approaching ASI era.

Specifically, we discuss two main points. First is the transformation of learning environments and spectator experiences driven by ANI. The widespread adoption of advanced analysis technologies has led to a "democratization of skills," eliminating geographical and environmental disparities. Additionally, the visualization of evaluation scores has opened the "black box" of the game, creating new entertainment value.

Second are the ethical and existential challenges posed by the ubiquity of ANI. The risk of "cheating via AI assistance" has forced a shift from traditional environments based on mutual trust to those requiring strict surveillance systems (Zero Trust). Furthermore, the existence of AI possessing "absolute answers" compels professional players to redefine their value beyond mere victory and defeat, questioning the very meaning of human play.

Through the process of friction and adaptation observed in the Shogi community, this research offers insights into the challenges and possibilities humanity will face in the approaching ASI era.

Keywords: ANI (Artificial Narrow Intelligence), ASI (Artificial Super

Intelligence), Democratization of Skills, Anti-Cheating Measures, Visualization of Evaluation, Computer

Shogi

An update to MCGS: A Minimax-based Combinatorial Game Solver

Mueller Martin(University of Alberta)

At CGTC V in Lisbon 2025, we introduced Version 1 of MCGS, our Minimax-based

Combinatorial Game Solver. In this update, we describe the work done over the last year, leading up to the

current version 1.5. This includes support for many more games, more algorithms, and many efficiency

improvements.

Keywords: MCGS, combinatorial game solver, algorithms

Generalizing OOOOOOB

Thotsaporn Thanatipanonda(Mahidol University

International College)

We consider the P and N-positions of the Nim-type game similar to Wythoff. The

game starts with $k$ piles of tokens, the players take turns removing 1 token from one pile or removing one

token from each pile (Version B of our 3 versions). The last player to move wins. In this talk, we'd

like to present the automated proof methodology. First we conjecture of the P and N-positions using the

computer program. Then we also write the program to prove the conjectures rigorously.

Semi-Perfect-Information Nim and Its Variants

Hironori Kiya(Osaka Metropolitan University)

We introduce an oracle model for imperfect-information games, with a focus on

Nim. In our model, heap sizes are hidden, while the oracle reveals position signals, e.g., the

Sprague–Grundy number. We ask which oracle information suffices to choose an optimal move from observation

alone, and we report basic properties on the feasibility of optimal play in Nim and its variants under this

model.

Keywords: Nim, Imperfect information

TBA

Ravi Kant Rai(Vidyashilp University)

Abstract will be provided soon.

Keywords: Combinatorial Games, Bidding Games

More Results on Modular Nim Games

Balaji Rohidas Kadam(Research scholar, Indian Institute

of Technology Madras, Chennai, INDIA)

Modular Nim is a classical impartial combinatorial game with many unresolved

instances. For a finite move set \(M=\{m_1,\dots,m_k\}\subset\mathbb{Z}\) and \(n\ge 1\),

\(\Gamma(m_1,\dots,m_k;n)\) denotes a game of Modular Nim played on a directed cycle with \(n\) vertices. In

2014, Tan and Ward proposed several conjectures about winning player of Modular Nim games with a two-element

move set, including conjectures for the families \(\Gamma(a,b;2b)\), \(\Gamma(a,b;2(a+b))\), and

\(\Gamma(2,b;2+2b)\).

In this work, we prove these conjectures and establish a general result that yields the complete solution of \(\Gamma(a,b;2b)\) as a special case. We also introduce and completely solve the family \(\Gamma(1,b;2b-1)\). In addition, we give an explicit winning strategy for the first player for games of the form \(\Gamma(M;n)\), where \(M\) consists only of odd integers and \(n\) is even. Finally, we complete the classification of the family \(\Gamma(2,b-1;b)\), resolving the remaining cases of a conjecture posed by Tan and Ward that was partially solved by Srinivas Arun in 2025.

In this work, we prove these conjectures and establish a general result that yields the complete solution of \(\Gamma(a,b;2b)\) as a special case. We also introduce and completely solve the family \(\Gamma(1,b;2b-1)\). In addition, we give an explicit winning strategy for the first player for games of the form \(\Gamma(M;n)\), where \(M\) consists only of odd integers and \(n\) is even. Finally, we complete the classification of the family \(\Gamma(2,b-1;b)\), resolving the remaining cases of a conjecture posed by Tan and Ward that was partially solved by Srinivas Arun in 2025.

Keywords: Geography game, Modular Nim game, Diamond Drop strategy

Download File

Twenty years of my research on combinatorial game theory with high school students

-Chocolate Games, Games with a Pass, Maximum Nim- (Invited Talk)

Ryohei Miyadera(Keimei Gakuin Junior and High

School)

I will talk about three topics: chocolate games, games with a pass, and Maximum

Nim. I have been researching these topics with my high school students for more than 20 years. These three

topics are related to each other. Arguably, I was the first in the world to take up combinatorial games as a

topic for a high school math research group and publish papers with students. My high school students and I

read about rectangular chocolate games twenty years ago, and rectangular chocolate games are disguised Nim.

These games are mathematically the same as three-pile Nim but have representations that differ from

classical Nim. It is often the case that a different representation offers a different path for research,

and this rectangular chocolate gave my students and me a perfect opportunity to conduct research. By

changing the shape of chocolates, we developed a variety of Nim variants and published nine articles on

chocolate games. We discovered the necessary and sufficient conditions for chocolate games to have the

Grundy-number formula described by the nim-sum, and some sufficient conditions for chocolate games to have a

formula for P-positions described by the nim-sum. About 10 years ago, we began studying games with a pass.

This pass move may be used at most once in the game and not from the terminal position. In the case of

classical Nim, the introduction of the pass alters the game’s mathematical structure, considerably

increasing its complexity, and finding the formula that describes the set of previous players’ winning

positions remains an important open question. We wondered why a pass move makes traditional Nim too

complicated and began studying many games with a pass, and found that Chocolate Game, Maximum Nim, Wythoff’s

Game, and Silver Dollar Game have formulas for P-positions when a pass is permitted. We discovered a

sufficient condition for chocolate games with a pass to have Grundy-number formulas. We also found a

sufficient condition for games in general to have formulas for P-positions, and well-known games such as

Wythoff’s Game, Silver Dollar Game, Maximum Nim, and Greedy Nim satisfy this condition. We also studied

Maximum Nim without a pass and discovered a fascinating relation between Maximum Nim and the Josephus

problem. We found a formula to calculate the P-positions of Maximum Nim without using recursion, which

enables us to efficiently determine the last remaining number in the Josephus problem. In Chess, Go, and

Shogi (Japanese Chess), there are many very young professional players, indicating the significant potential

of young talent in the study of games. I hope that many young people will discover many new things in

combinatorial games in the coming decades.

The Invariance Reduction Process – a New Tool to Solve Circular Nim and Related Games

Silvia Heubach(California State University Los

Angeles)

We introduce the notion of invariant vectors of a game and develop the Invariance

Reduction Process, which first uses reduction of positions via invariance and then zero and merge reductions

of games to arrive at smaller, solved sub-games for closed subspaces of the positions. This process makes it

much easier to prove that there are moves from N-positions to P-positions, and can also be used in some

cases to show that there are no moves between P-positions. This process is suitable for all variations of

Nim whose rule sets form a simplicial complex. We rephrase Simplicial Nim as Set Nim and derive results on

the structure of the P-positions in terms of invariant vectors, without needing the background and notation

of simplicial complexes. We apply the Invariance Reduction Process to derive results on the P-positions of

the family of Path Nim games where play is allowed on at least half the stacks, as well as for the Circular

Nim games CN(n,k) with n=7, k=3 and n=8,k=3.

Keywords: Combinatorial games, Invariance Reduction Process, Set Nim,

Simplicial Nim, Path Nim, Circular Nim

Scoring Nim

Hiromi Oginuma(Nara Women's University)

Nim is a well-known combinatorial game, in which two players alternately remove

stones from distinct piles.

A player who removes the last stone wins under the normal play rule, while a player loses under the mis\`ere play rule.

In this talk, we propose a new variant of Nim with scoring that generalizes both the normal and mis\`ere play versions of Nim as special cases.

We discuss theoretical aspects of this extended game and present some results on its fundamental properties, such as optimal strategies and payoff functions.

A player who removes the last stone wins under the normal play rule, while a player loses under the mis\`ere play rule.

In this talk, we propose a new variant of Nim with scoring that generalizes both the normal and mis\`ere play versions of Nim as special cases.

We discuss theoretical aspects of this extended game and present some results on its fundamental properties, such as optimal strategies and payoff functions.

Keywords: Combinatorial game theory, Impartial game, Nim, Scoring

game, Optimal Strategy

Gibbard-Satterthwaite Model as a Combinatorial Game

Atsushi Iwai(Gunma University)

This study presents a simple method for linking social choice theory to

combinatorial game theory. The author utilizes the framework of the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem in social

choice theory as a primary example. While several fundamental concepts of the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem

have previously been adapted into the framework of 2-by-2 normal-form games, this study extends that

application to simple combinatorial games and demonstrates the typical consequences. From the perspective of

advancing social choice theory, applying concepts from combinatorial game theory appears to be a fruitful

endeavor, though the benefits may not be as significant in the reverse direction.

Keywords: social choice theory, combinatorial game,

Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem

The rulesets Expansion and Void Expansion

Aditya Khambete(IIT Bombay)

We define the partizan placement ruleset Expansion, and it’s all small variant

Void Expansion. Expansion is played on an m×n grid, where players place stones on all orthogonal squares to

any connected component of their own color. In Void Expansion, you may instead place a single stone on any

disconnected empty square. Consider Expansion: we prove that all dyadic rational values can be achieved on

row boards (1×n). In the case of Void Expansion we conjecture that arbitrarily large atomic weights appear

on row boards; with a game value of ↑n .

Play the game here: https://adityak1729.github.io/Expansion/

Play the game here: https://adityak1729.github.io/Expansion/

Keywords: Combinatorial Game Theory, Partizan Placement Game, Dyadic

Rational Value, Atomic Weight

Analysis of Blippers and Flippers: 2 loopy placement games with elimination mechanics

Parth Sarda(IISER Pune)

We introduce and analyze two loopy combinatorial games, Blippers and

Flippers,which belong to the class of placement games with dynamic elimination mechanics.

Both games are played on finite grids where players alternately place stones of their color, but differ in their elimination rules. In Blippers, pairs of orthogonally adjacent stones of the same color with no other same-color orthogonal neighbors simultaneously

disappear (”blip”). In Flippers, when two stones of the same color become orthogonally adjacent, the previously placed stone disappears (”flips”), unless there exists a third

stone of the same color orthogonally adjacent to either stone in the pair.

We establish fundamental results about the outcome classes of these games on rectangular grids, proving that for any t × x grid where t, x ∈ [2, n], the game has a P-position (second player win) when tx is even and an N-position (first player win)

when tx is odd. We further investigate the loopy nature of certain game positions and provide a comprehensive analysis using tools from combinatorial game theory,we can assign precise algebraic values to these positions. This analysis emphasizes the roles of Stoppers, the Onside/Offside rule, changed outcome classes, the Sidling Theorem, and atomic weights to reveal the strategic nature of these loops.

Both games are played on finite grids where players alternately place stones of their color, but differ in their elimination rules. In Blippers, pairs of orthogonally adjacent stones of the same color with no other same-color orthogonal neighbors simultaneously

disappear (”blip”). In Flippers, when two stones of the same color become orthogonally adjacent, the previously placed stone disappears (”flips”), unless there exists a third

stone of the same color orthogonally adjacent to either stone in the pair.

We establish fundamental results about the outcome classes of these games on rectangular grids, proving that for any t × x grid where t, x ∈ [2, n], the game has a P-position (second player win) when tx is even and an N-position (first player win)

when tx is odd. We further investigate the loopy nature of certain game positions and provide a comprehensive analysis using tools from combinatorial game theory,we can assign precise algebraic values to these positions. This analysis emphasizes the roles of Stoppers, the Onside/Offside rule, changed outcome classes, the Sidling Theorem, and atomic weights to reveal the strategic nature of these loops.

Keywords: Combinatorial game theory, optimization

Download File

Maker-Breaker s-of-k games

Miloš Stojaković(University of Novi Sad)

We introduce a general framework for positional games in which players score

points by claiming a prescribed portion of each winning set, extending the notion of scoring Maker–Breaker

games. We investigate the impact of strategy restrictions on the achievable score, analysing these games

both under optimal play and under the additional constraint that Maker is restricted to a pairing strategy.

We comprehensively study games where the boards are regular grids, which provide a natural and uniform setting for illustrating the framework. After developing several general tools for the analysis of both scores, we complement them by a number of ad-hoc strategies tailored for particular cases of these games, to obtain both upper and lower bounds for the two scores on triangular, square, rhombus and hexagonal grids.

We comprehensively study games where the boards are regular grids, which provide a natural and uniform setting for illustrating the framework. After developing several general tools for the analysis of both scores, we complement them by a number of ad-hoc strategies tailored for particular cases of these games, to obtain both upper and lower bounds for the two scores on triangular, square, rhombus and hexagonal grids.

Keywords: positional games, Maker-Breaker games

Extension of Set Nim to Partizan

Matthieu Dufour(University of Quebec in Montreal)

Abstract will be provided soon.

Keywords: Extension of NIm game, Partizan

Grid Nim

Ruchir Mital Parekh(IIT Bombay)

Grid Nim, a two-player combinatorial game played on an m*n grid, where some(all)

blocks of the grid have tokens. Right can remove any number of tokens from a single row, and Left can remove

any number of tokens from a single column. Although the game positions are significantly complicated due to

a significantly large number of options, it is possible to predict the player's advantage using a

simple formula. The main result proves that the advantage of a player depends only on the difference in the

number of non-empty rows and columns in the game.

Further, attaching a link of a playable version of the game (the game was earlier called A different Nim, but the rules remain the same) https://butterknifees.github.io/different-nim/

Further, attaching a link of a playable version of the game (the game was earlier called A different Nim, but the rules remain the same) https://butterknifees.github.io/different-nim/

Keywords: Combinatorial Game Theory, Game of Nim